Cullen waders - Red neck Stint and Red Capped Plover by Adrian Martins courtesy North Central Catchment Management Authority

Water is the magic ingredient in the Australian landscape - its presence a flag that signals to our plants and animals when to bloom and breed and travel. But with many river systems altered beyond recognition, is there still a future for the many creatures that rely on the highs and lows of naturally flowing water? BirdLife Australia’s Darren Quin and the VEWH’s Bruce Paton examine the promising results of environmental water releases at Victoria’s Lake Cullen and reveal that all is not yet lost.

If you were to jump in a time machine and travel back a few hundred years, you would find a landscape very different to the one we live in now. You would see rivers that ran low in the hotter months of summer and filled up when it rained in winter; that often pulsed with water gushing down from rainfall higher up on their catchments, and that sometimes spilled over the banks of waterways onto surrounding floodplains to flood lakes and wetlands.

This is the world that our native species have evolved to flourish in - with wet winters and dry summers, punctuated by rises and falls in water levels that did everything from add nutrients to aquatic habitats to provide natural signals that told animals when to migrate and breed.

Fast forward to the present day and it is a different world. Many of our river systems have been modified as the country has grown, to provide water for towns, industry and food production. Instead of water flowing naturally through the landscape, water is now captured in dams and weirs, and then delivered via pipes and man-made channels. As a result, some of our rivers give up more than a third - and sometimes half - of the water that would have naturally flowed in them throughout each year. These changes have interrupted many of the natural river and wetland processes needed by native plants and animals to survive, feed and breed - leaving many species - particularly wetland birds - in crisis.

This is where environmental watering comes in. A system which seeks to alleviate the unnatural pressure exerted on wetlands and rivers by providing targeted flows to significant sites, water for the environment has been a part of policy in Victoria since the 1990s, with environmental managers across the state using water to protect threatened species, support natural ecosystems, and help protect cultural values.

But how well does it work? The recent filling of Lake Cullen in northeast Victoria provides an exciting success story, and shows the myriad ways targeted environmental watering can help native birds, fish and other species to thrive.

Caring for Cullen

To say that the 630-hectare Lake Cullen, 20 kilometres northwest of Kerang, is important for wetland birds would be understating the case. It is one of the 23 wetlands forming the Kerang Wetlands Ramsar Site, is part of the North Victorian Wetlands Key Biodiversity Area and is listed under the Directory of Important Wetlands in Australia as a nationally significant wetland in its own right. In its original state, the abundance of food at the lake would have attracted tens of thousands of waterbirds—everything from freckled ducks to magpie geese - with a huge variety of different species coming and going as the water levels flooded and dried over time.

But as is the case with so many other wetlands in Australia, Lake Cullen has been dramatically reshaped over the past century. The unique ecological characteristics that the Lake supports, including intermittent salinity, variable water depths and a diversity of vegetation, were significantly altered after it was used for freshwater storage in the 1920s. Even after 1973, when the Lake ceased to be part of the Torrumbarry Irrigation System, it was still effectively disconnected from its floodplain system as part of the Loddon and Avoca River catchment and was very rarely inundated by natural flows.

Then, in 2013, the North Central Catchment Management Authority developed the Lake Cullen Environmental Water Management Plan. The idea was to restore a natural water regime for the wetland over a ten-year cycle and recreate the refuge the lake once provided for wetland birds of every type.

But it wasn’t as simple as just adding water.

Environmental watering is about mimicking natural processes, not just following a recipe which says turn the tap on every year on the first of September. In natural systems there’s built-in chaos. Wetlands might half fill sometimes then dry, then completely fill at others, or remain dry for long periods. This chaos stimulates diversity and forms habitat niches created by the different water levels.

Overall, it's the entire environmental flow regime that matters, including the volume, timing, duration, frequency and quality of flows that are provided - different combinations of these provide a range of different benefits for ecosystems.

At Lake Cullen environmental water was piped in over the spring of 2016 and was intermittently topped-up during the following months after heavy rainfall in September and October 2016 resulted in the flooding of the Avoca River and the Avoca Marshes and Lake Bael Bael. About 20,000 megalitres of water filled the system, and this rare inundation gave BirdLife Australia, the local CMA and the VEWH the opportunity to record, evaluate and identify the responses of waterbirds to wetting and subsequent drying over 2018 and 2019.

The birds come back

The Lake Cullen Project, which mobilised volunteers from BirdLife Australia and the Mid-Murray Field Naturalists to monitor birds at the wetland over the course of the most recent rounds of environmental watering, has recorded some fantastic results. Kicking off with a workshop attended by 50 people from around the Kerang region in early 2017, the committed citizen scientists have gone on to conduct monthly surveys in conjunction with local ecologists, which reveal the extent that environmental watering has supported both waterbird foraging and breeding habitat, and a high abundance and diversity of waterbird species.

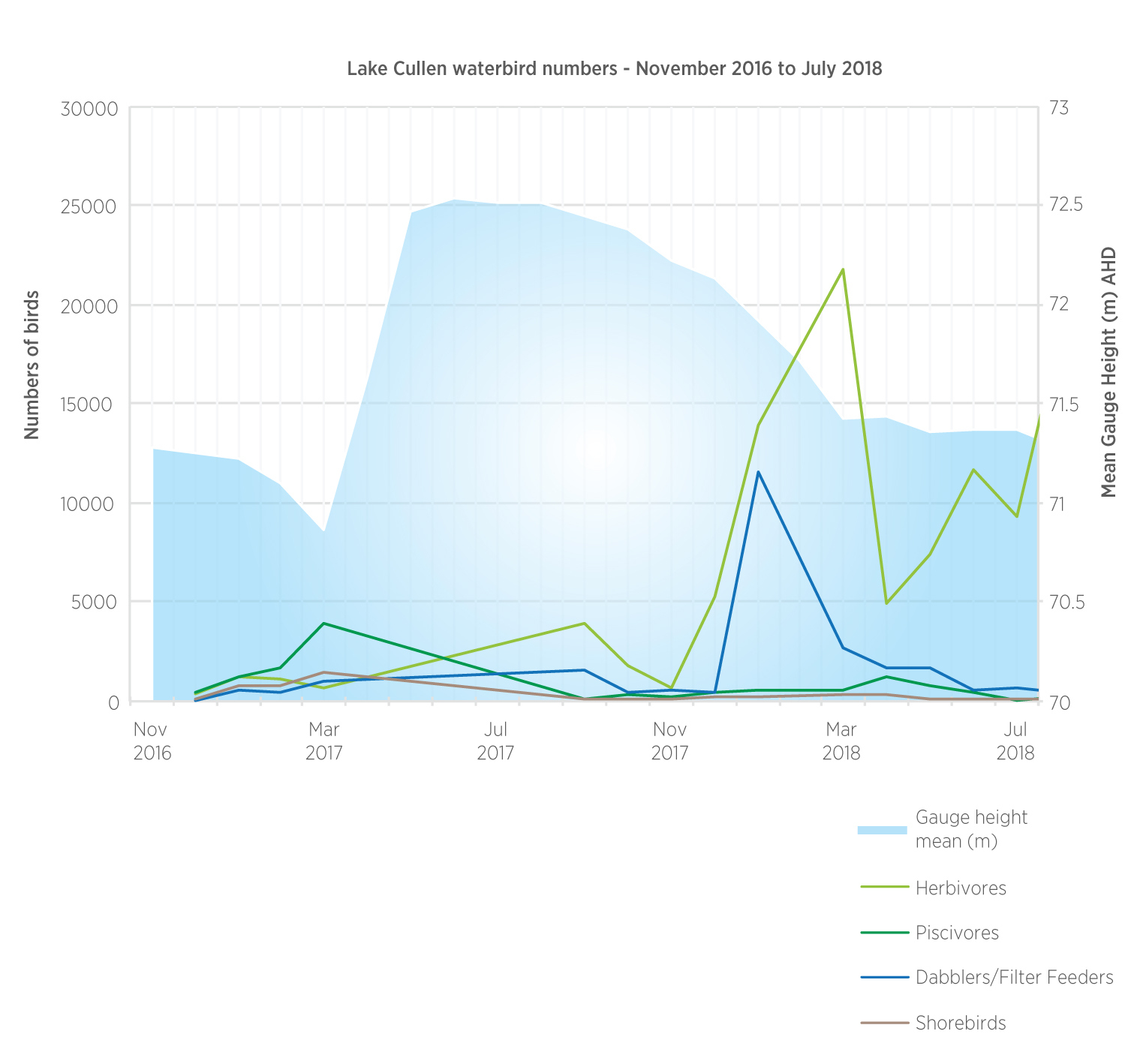

One thing that is very clear is how different water levels provide different things for different types of birds. At the end of summer, in March 2017, when the water levels in the wetland were at their lowest, mature fish and frog populations concentrated - providing a perfect smorgasbord for thousands of pelicans and hundreds of cormorants. The low water also meant that the edges of the lake were exposed, and black-winged stilts and red-necked avocets arrived in high numbers to feast on insects in the muddy margins.

Then, as water flooded the wetland over the autumn and through the winter of 2017, the shorebirds and piscavores disappeared. The high water submerged exposed vegetation, which then decomposed, reanimating larval insects and spawning another generation of submerged vegetation growth and aquatic fauna.

In early 2018, as the water once again became shallower, aquatic vegetation rose closer to the surface, and insects matured and concentrated, waterbird numbers exploded. This was when the herbivorous, dabbler and filter-feeding birds flocked to Cullen - with thousands of ducks and swans and grebes descending on the wetland. January and March 2018 saw a packed house, with counts of 27,023 and 26,736 waterbirds respectively. Grey teal and Eurasian coots were particularly abundant, with 11,420 teal counted in January 2018 and 19,540 coots counted in March 2018.

But it’s not only common birds that have flocked back to the Lake - 18 species listed as threatened under Commonwealth or Victorian legislation have also been spotted. Of particular note are the high numbers of critically endangered Australasian bitterns that have been recorded, with at least 16 birds flushed from the reedbeds in May 2017 and 14 in May 2018. With total numbers of bitterns estimated to be as low as 800, the birds at Cullen represent a large chunk of the remaining population. Interestingly, the water level at the lake does not appear to affect whether the bitterns are present or not, it is thought that the healthy reedbeds are what attracts these elusive birds.

And the happy results just keep coming. Up to 150 threatened freckled ducks were counted in February 2018. The magpie goose, also listed as threatened under Victorian legislation, has returned to the Kerang area after an absence of many years, with three geese recorded breeding at Lake Cullen in November 2017 and November 2018. A pair of brolgas were resident from January to March 2018, as were 120 eastern great egrets.

Rare migratory waders have also called in on Lake Cullen, including a single black-tailed godwit, which visited the lake from January to March 2018 and again in September 2018. Other shorebirds spotted at the wetland include a little curlew, red-necked stints and sharp-tailed sandpipers. A trans-Tasman migrant has also gotten in on the action, with a single double-banded plover spotted in May 2018.

So, what’s next for Cullen?

A top-up of water began on 5 October 2018, with 150 megalitres a day flowing in to fill the wetland. The additional water is on the recommendation of the Environmental Water Advisory Group and is aimed at providing habitat for waterbirds seeking refuge from the current drought afflicting the south-eastern states. Already, black-tailed godwits, glossy ibis, whiskered and gull-billed terns, yellow-billed spoonbills, and many other species have been spotted since the water again began to flow. And the dedicated local volunteers who have been undertaking monthly surveys at the Lake will continue their work, ensuring that bird numbers and diversity will be recorded as the water rises and falls over the coming months and years.

All of this is part of Victoria’s wider Seasonal Watering Plan, released on 30 June each year and detailing environmental watering plans for rivers, creeks, wetlands and floodplains across the state under a range of weather condition scenarios - dry, average and wet. As has been discovered with Cullen, nature doesn't keep to strict timelines, so potential environmental watering scoped in a seasonal watering plan may begin before, or continue beyond, the year of the plan. But though nature keeps her own timetable, the results at Lake Cullen tell us is that environmental watering works, and that even in our heavily altered and unnaturally ordered landscapes we can restore the chaos that our wildlife needs.

Story reproduced with the permission of Birdlife Australia.

To learn more about the Lake Cullen Project check out the Lake Cullen – e water for waterbirds video on BirdLife Australia’s YouTube channel.