Surveys over five years at Barmah Forest show a connection between environmental watering of the wetlands and waterbird fledging success.

Barmah Forest's shallow wetlands provide breeding habitat for colonial waterbirds. These are birds that nest in groups (such as the Australian white ibis, straw-necked ibis and royal spoonbill).1,2 If wetlands are flooded for 3–4 months, they create ideal conditions for the birds to nurture their young from egg to flight, a life stage known as fledging.

The Goulburn Broken Catchment Management Authority (CMA) has monitored nesting behaviour in response to environmental watering since 2011.2 Aerial surveys, site visits and remote cameras have tracked water depth and bird response.

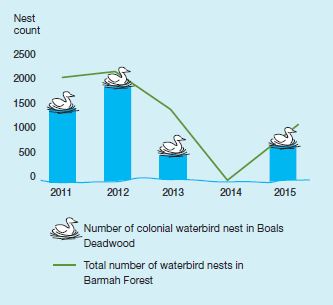

One wetland, Boals Deadwood, has been home to most of Barmah Forest's waterbirds in the last five years, as Figure 1 below shows. In a successful breeding season, two or three birds may fledge from each nest.

Figure 1. Colonial and other waterbird nests, Boals Deadwood and Barmah Forest

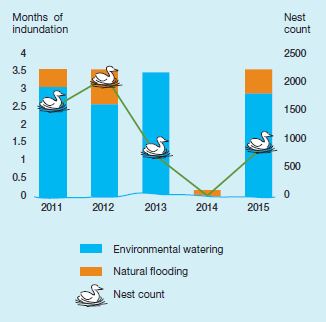

Environmental watering in Boals Deadwood maintained a depth of 0.5 m for 3–4 months, emulating more natural conditions. While how much environmental water is delivered each year varies according to rainfall and natural inflows, sufficient water is necessary for waterbirds to breed.3,4

In four of the last five years (between 2011–15), the number of nests in Boals Deadwood was highest when it was flooded for 3–4 months, as Figure 2 below shows.

While the right triggers for nesting—early-season flooding, water temperature and day length—occur most years naturally, environmental watering has been essential to achieve the 3–4 month flooding needed for fledging.5

Goulburn Broken CMA Project Officer Lisa Duncan says the one year the forest didn't receive environmental water had a significant effect on breeding. "We saw 500 ibis nests abandoned in 2014 when seasonal conditions changed in the wetland and we were unable to arrange delivery of environmental water in time."

White ibis chicks at Boals Deadwood wetland, by Keith Ward

White ibis chicks at Boals Deadwood wetland, by Keith Ward

White ibis, straw-necked ibis and royal spoonbill represent half-to-all of the total population of nesting waterbirds throughout the forest.1,2

By knowing the number of nesting waterbirds and monitoring fledging, environmental water managers can respond to changes regularly. For example, they might adjust the volume of water delivered to avoid nests being inundated or abandoned.

Birds are an important part of wetlands and environmental water maintains the range of plants and animals needed to sustain their habitat and foraging grounds. Environmental watering over the past five years has supported thousands of waterbirds to fledge successfully.6

1 Unpublished data reports, Goulburn Broken CMA.

2 D. J. Leslie, 2001, Effect of river management on colonially-nesting waterbirds in the Barmah–Millewa Forest, South-Eastern Australia. Regulated Rivers: Research and Management 17: 21–36.

3 A. D. Arthur, J. R. Reid, R. T. Kingsford, H. M. McGinness, K. A. Ward & M. J. Harper, 2012,Breeding flow thresholds of colonial breeding waterbirds in the Murray-Darling Basin, Australia. Wetlands, 32(2), 257-265.

4 K. A Ward, 2015, Environmental Water Allocations in the Barmah-Millewa wetlands. Floodplain Ecology Course.

5 R.T. Kingsford, J. L Porter & A. Wetlands, 2012, Survey of waterbird communities of the Living Murray icon sites, November 2011. Australian Wetlands and Rivers Centre, University of New South Wales, Report to Murray-Darling Basin Authority.

6 GB CMA & OEH, 2016, Barmah-Millewa Forest Seasonal Watering Proposal 2016-2017. Prepared 14 April 2016. Goulburn Broken CMA, Shepparton, and NSW Office of Environment & Heritage, Moama.