The wetlands and surrounding land in the central Murray region hold great significance for the Traditional Owners: the Barapa Barapa, Wamba Wemba, and Yorta Yorta peoples. Their traditional knowledge is a living culture evident throughout the landscape in tree markings, significant cultural sites, and cultural tools for cultural practices. The rivers and floodplains are a food and fibre source and contain many sites of significance (such as campsites and meeting places).

Environmental watering supports values including native fish, waterbirds and turtles, and it promotes the growth of culturally important plants that provide food, medicine and weaving materials for Traditional Owner groups. The presence of water itself can be a cultural value, as well as the quality of the water: healthy water promotes a healthy Country.

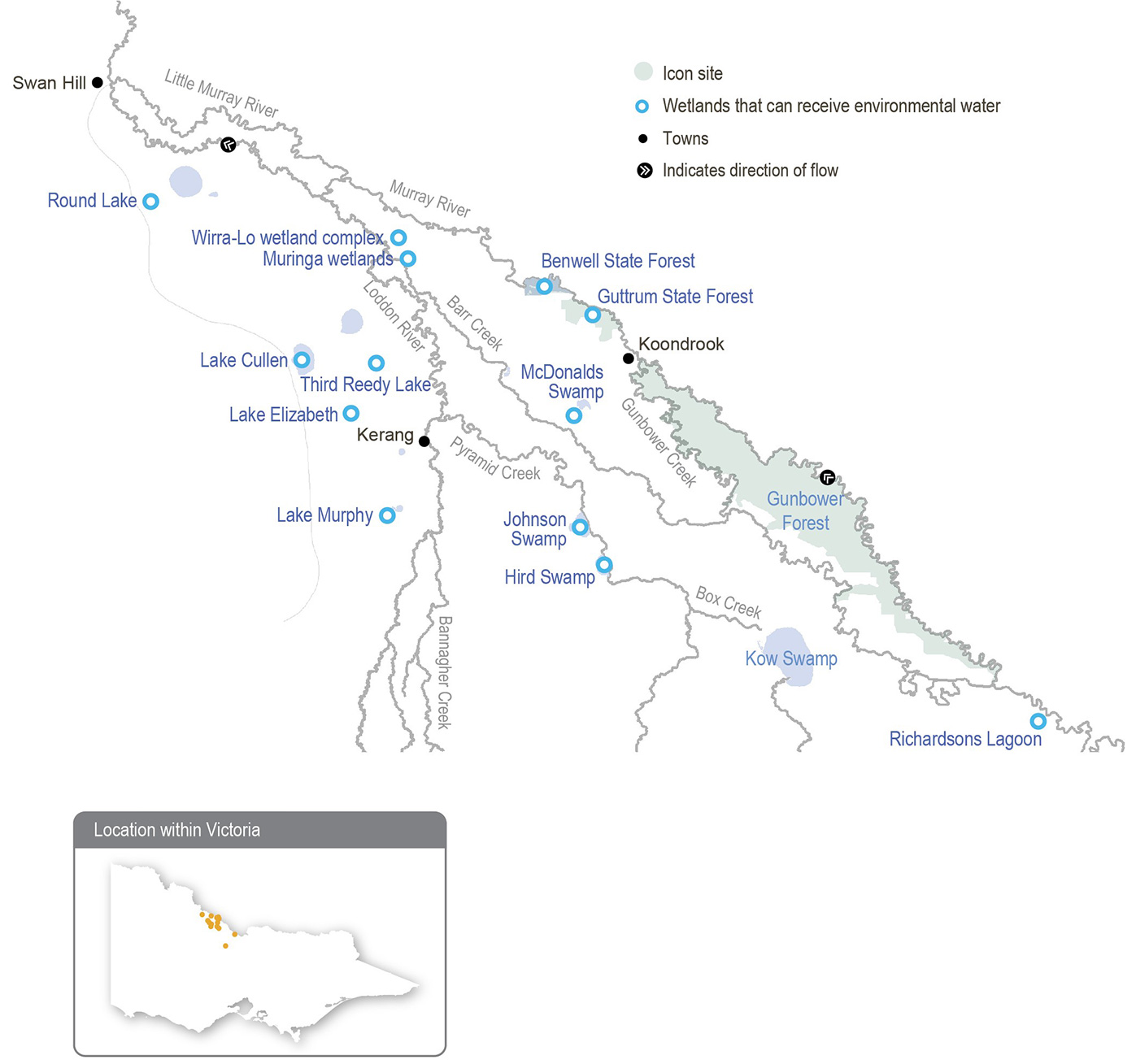

In early 2023, Barapa Barapa and Wamba Wemba Traditional Owners joined North Central CMA staff on Country to reflect on environmental water management in the central Murray wetlands, including plans for 2023-24. This included a day in Guttrum Forest and another day visiting Johnson Swamp, McDonalds Swamp, Third Reedy Lake and Lake Cullen. Topics of discussion included:

- The impacts of the 2022-23 floods on the wetlands, both positive (such as healthy fringing trees and lignum) and negative (such as carp and hypoxic blackwater)

- The proposed schedule for wetland watering and wetland drying in 2023-24; Barapa Barapa and Wamba Wemba Traditional Owners supported the plans for 2023-24 and noted that floods had provided an important ecological reset for many of the wetlands, and the proposed watering schedule will build on this

- Aboriginal Waterways Assessments (AWAs) and the aspiration for Barapa Barapa and Wamba Wemba Traditional Owners to undertake AWAs at several of the central Murray wetlands in the future during wet and dry phases

- The benefits that water for the environment has delivered to the wetlands over the years. Traditional Owners said that water delivery to Johnson Swamp, combined with tall marsh and lignum slashing, has created a more open-water environment that has attracted waterbirds. Similarly, Traditional Owners involved in tree planting at McDonalds Swamp in 2018 were impressed by the growth of the river red gums and the expansion of lignum and cane grass due to environmental watering

- Concerns about the impact of duck hunting on waterbird numbers at several central Murray wetlands and concerns about rabbits harming culturally significant locations at Lake Cullen

- Guttrum Forest (particularly Reed Bed Swamp) and the need to dry it out in the coming months to control carp and allow the removal of protective nets that have helped new vegetation establish. The plan is to deliver environmental water to Reed Bed Swamp in 2023-24 to build on the positive outcomes from previous years (such as the growth of aquatic vegetation and tree canopies)

Increasing the involvement of Traditional Owners in environmental water management and progressing opportunities towards self-determination in the environmental watering program is a core commitment of the VEWH and its agency partners. This is reinforced by a range of legislation and policy commitments, including the Water Act 1989, the Victorian Aboriginal Affairs Framework, the 2016 Water for Victoria, the Water is Life: Traditional Owner Access to Water Roadmap 2022, and in some cases, agreements under the Traditional Owner Settlement Act 2010.

Where Traditional Owners are more deeply involved in the planning and/or delivery of environmental flows for a particular site, their contribution is acknowledged in Table 5.2.10 with an icon. The use of this icon is not intended to indicate that these activities are meeting all the needs of Traditional Owners, but is incorporated in the spirit of valuing that contribution.

| Watering planned and/or delivered in partnership with Traditional Owners to support cultural values and uses |

Barapa Barapa and Wamba Wemba input to watering actions for Guttrum Forest in 2023-24

Delivery of water for the environment to Guttrum Forest during 2023-24 has been planned in conjunction with the Barapa Barapa and Wamba Wemba peoples, for whom the wetlands and surrounding forest are places of high cultural significance. Traditional Owners are an important part of Guttrum Forest planning and management and have been directly involved in the delivery of environmental flows to Reed Bed Swamp in 2019-20 and 2021-22. In 2022-23, no environmental water was delivered to Reed Bed Swamp due to large-scale natural flooding.

Barapa Barapa and Wamba Wemba collaborate with waterway managers to ensure that during watering events, their cultural heritage is protected and that the hydrological needs of important cultural values (such as food and medicinal plant species, scar trees and ring trees) are supported through the timing and duration of planned watering actions to the forest.

Table 5.2.9 outlines the values and uses considered in the planning for and management of water for the environment at Guttrum Forest in 2023-24.

Table 5.2.9 Barapa Barapa and Wamba Wemba cultural values and uses at Guttrum Forest

| Value/use | Considerations |

|---|

Food, fibre and medicinal plants | - A winter/spring fill followed by top-ups, as required, will ensure that the duration of wetting will be long enough to support aquatic vegetation during its optimal growth period. Allowing the wetland to draw down before summer will also promote cultural plants on the mudflats in these areas. With annual watering in recent years and natural events like the October 2022 flood, harvesting cultural plants is likely to be possible within a matter of years.

|

Cultural heritage | - Watering of Reed Bed Swamp supports fringing large old trees, including a couple of ring trees and scar trees. The condition of these trees was seen to improve following previous watering.

|

Spiritual wellbeing | - The improvement in the condition of the wetland and the presence of water and moisture contribute to a sense of spiritual wellbeing.

|

Sharing cultural knowledge | - The Traditional Owners provide support and advice about what ecological values to target: that is, they provide information about what the wetland used to look like and what values it previously supported.

- Traditional Owners have been present during the set-up of infrastructure and have been able to advise about avoiding impacts on their cultural heritage.

|

Employment opportunities | - Traditional Owners want to become more involved in the management of their Country through increased employment opportunities (such as ecological and cultural monitoring). This has occurred as part of previous watering of Reed Bed Swamp.

|

Cultural landscape | - Maintaining the open-water habitat and mudflats underneath will be difficult if the river red gum saplings that germinated in recent floods are not removed. This is important for maintaining the cultural landscape and access to food and medicinal resources.

|

Cultural practice | - In 2019-20 when water for the environment was first delivered in Guttrum Forest, a smoking ceremony and celebration were held to welcome the water back to the wetland. The Traditional Owners have indicated that this should be a regular activity each year when water is delivered, as it is something that their ancestors would have done when the floodwaters arrived and would represent a restoration of an important cultural practice.

- Another priority in 2023-24 is to provide more opportunities for women to return to Country and undertake cultural practices such as weaving, emu egg carving and discussion of the wetlands’ health as it relates to women’s business.

|